Joints

Joints

Joints provide another type of constraints and are used to connect several objects. The properties of the connections depend on the selected joint kind.

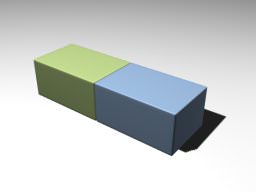

Fixed Joint

Fixed joints connect two objects in a manner that strictly preserves their positions with respect to each other.

|

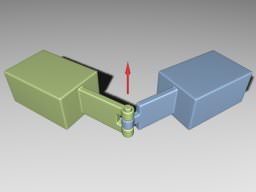

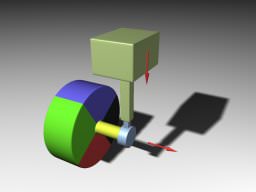

Hinge Joint

Hinge joints allow the connected objects rotate along the axis specified with the joint.

|

|

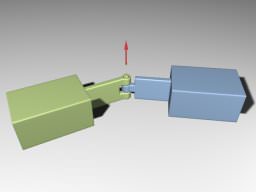

Ball Joint

Ball joints provide a point around which the connected objects can rotate.

|

|

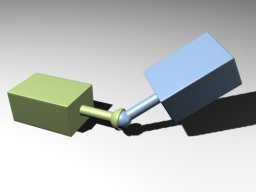

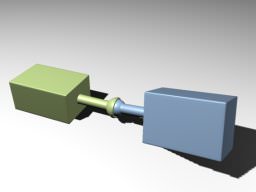

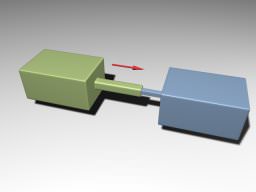

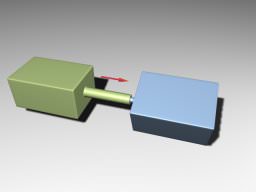

Prismatic Joint

Prismatic joints allow moving along the joint axis.

|

|

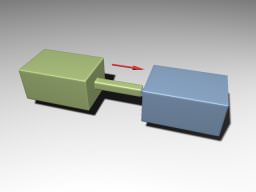

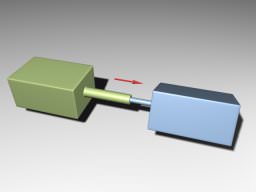

Cylindrical Joint

Cylindrical joints are like prismatic ones, but also allow rotating along the axis created with the joint.

|

|

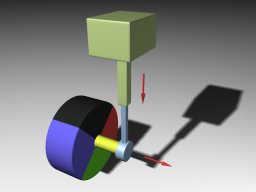

Suspension Joint

Suspension joints are used to create wheels.

|

|

Common Joint Properties

Joints of all types can be destructed, if the impulse conveyed to them is too large.

Joints can have motors and springs associated with them. There are linear and angular motors that exert a limited force to a joint, pushing or rotating connected objects. Springs try to keep the objects connected with a joint at some specific distance (linear) or angle (angular). The behavior of a particular spring depends on its rigidity and damping coefficient.

Joints, like collisions, are calculated iteratively. However, if an LCP-based solver is used, their influence is computed along with collision detection, and in case of sequential impulse-based calculations, they are computed separately. Again, correctness of joint behavior depends on the number of iterations. Another important effect of the iterative calculations is that if two objects with a large mass ratio are joined, accuracy may also suffer.

Vehicles

Vehicles are also described separately, as they are important in real-time games. In general, there are two ways to simulate a moving vehicle.

The first way assumes that wheels of the vehicle are attached to its body using joints (wheel joints). The joints usually have a motor associated with them, which rotates the wheels and pushes the car forward. As the wheels are "real", collisions with objects on the ground are handled correctly. For example, such car runs on a curb smoothly.

If the other approach is used, the wheels are made purely virtual: they are simply drawn but do not interact with the surface of the road. Instead, rays are cast down from the car body to detect surface unevenness. As the wheels do not really interact with the surface, steep changes of the terrain are not handled accurately. This makes such method appropriate for racing cars, as they run on smooth-faced surfaces, however, on cross-country terrains it may not work correctly.